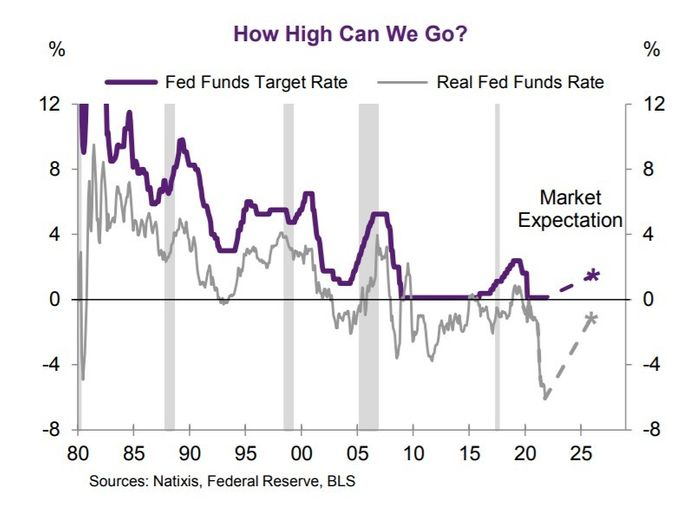

As the signals from the Federal Reserve become louder and louder that interest rates will be hiked next year, the question for markets becomes less about when and more about, how high.

Nearly every rate-hike cycle since the 1970s has resulted in successively lower peaks. That's logical, because inflation also has had lower peaks.

"In essence, a secular decline in inflation has mitigated the need for monetary policy makers to lift official interest rates as much as previous business cycles," said Joe LaVorgna, the chief economist of the Americas for Natixis Corporate and Investment Banking, who also was chief economist for the White House National Economic Council in the latter days of the Trump administration.

Markets have learned. Measured by five-year overnight index swaps, traders expect the next rate hike cycle to peak at just 1.45%. And adjusted for inflation, real rates are forecast not to get into positive territory in this business cycle.

LaVorgna said markets may be in store for a rude awakening. "But unprecedented fiscal and monetary stimulus since COVID may have reversed the post-1980s secular downtrend in inflation. If this is the case, then the real fed-funds rate eventually needs to get back into positive territory to dampen inflationary pressure," he said.

LaVorgna said the bond market isn't yet prepared. And to MarketWatch, he said neither is the stock market. The end result for equities? "Eventually a serious compression in multiples," he said in an email. The last reading for the Shiller price-to-equty ratio was a staggering 39.